America's Forgotten Sense of Place

Yesterday's world was real, and it's up to us to bring it all back

There is a diner in my memory. A place where the coffee is black as oil and the waitress knows your name by the third visit. The kind of place where truckers and ranchers sit at the counter next to college kids driving home for Christmas break. Where the pie case held actual pie made by someone’s grandmother that morning. An old jukebox in the corner that played Merle Haggard. The walls are decorated with faded photographs of the town’s glory days.

It’s not a real place. It’s part of a hazy collection. Pieces of a hundred small “worlds” that sit inside a time capsule in the back of my mind. A swirl of vague memories. A lost time and place that can only be seen after you drive by another Starbucks.

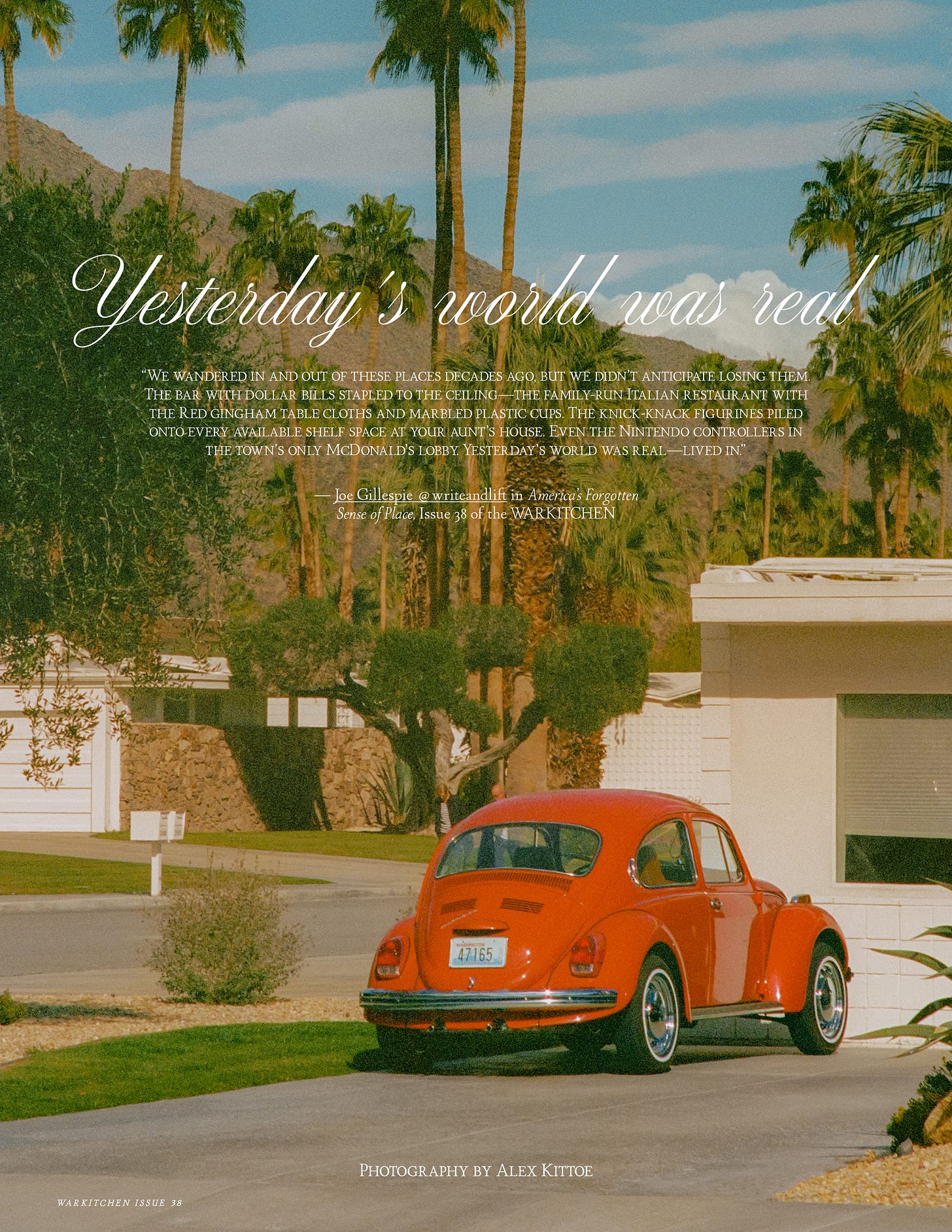

We wandered in and out of these places decades ago, but we didn’t anticipate losing them. The bar with dollar bills stapled to the ceiling—the family-run Italian restaurant with the red gingham table cloths and marbled plastic cups. The knick-knack figurines piled onto every available shelf space at your aunt’s house. Even the Nintendo controllers in the town's only McDonald’s lobby. Yesterday’s world was real—lived in.

“I miss this imperfection; character, natural materials, kitsch, color and the millions of small noisy details that elevated the mundane world to something unique and unreplicable. I feel like I’m trapped in a train car, looking through the fogged glass. Apparitions of bustling shopping malls, church steeples, bowling alleys, family restaurants, and busy, unchanged, downtowns fading beyond comprehension into a decaying memory."

I’m moving toward some unknown place, a construct that I vaguely recognize. It’s not the past. It’s not the sleek sci-fi future as imagined in the late fifties. The homes are drab, cheap, colorless, and identical, dropped into their locations straight from algorithm-designed blueprints. The parking lots are ever-expanding. The sidewalks are broad and empty. The stores smell the same and the same music plays. The restaurants are sterile and bright and full of clanking metal chairs that hurt your ass after five minutes. The employees look up from their phones with the same eyes.

Today, everywhere we go, there is a blurring of sense of place; in our homes, businesses, and public spaces. A slow, methodical murder of character. The corporate flattening of everything that once made somewhere worth being, and worth remembering.

This is the story of every place in America.

You Don’t Know What You’ve Got

Let’s get it out of the way and point our finger at the obvious. Globalization.

No other change in the last forty-plus years has accelerated the death of character and aesthetic heritage in American communities more. Cheap materials. Economic growth. Easy and replicable.

Markets (no matter how big or small) crave stability and managed risk. You find something that “works” once, and you replicate it. Again. And again. And again. For the deep-pocketed developers, craftsmanship cannot be applied at scale. What matters is speed. Supply chain management. A worthwhile investment.

The same systems and mechanics that can erect a massive strip mall in a year, can be used for our cars, furniture, homes, and stores. When money is involved, the proof of concept doesn’t get put back in the box. It spreads like a crawling lava flow; through cities first, and then the affluent suburbs, before reaching the quiet places far from anywhere else.

Slow change sneaks by us.

In the small town I was raised, the opening of a popular franchise used to excite us. We didn’t have to drive twenty minutes to get orange chicken from the small family owned Chinese restaurant anymore. We could buy it down the street; and it tasted exactly the same at this chain as it would from another location in the country! Then came the big box retail store. And another Starbucks. And the car wash chain—we’d all heard the catchy jingle on the radio. “And they used fancy new robots to wash your car instead of people!” The list goes ever on and on.

In the late 90s and early 00s, nobody asked: “At what cost to us?” We felt like we were catching up to the rest of suburbia. Parents of small families could breathe a sigh of relief knowing that long trips “to the city” to stock up on a month’s worth of bulk groceries and supplies were a thing of the past. Teenage girls no longer had to drive to the mall to get the new brands. Walmart and Target carried everything—and more—that the small local shops did, and at a cheaper price.

You don’t know what you had until it’s ripped from you. Convenience is an easy sell. And as Thomas Sowell said, “there are no solutions, only tradeoffs.” You can’t hold onto the soul of a place while simultaneously selling it out.

Inertia of Change

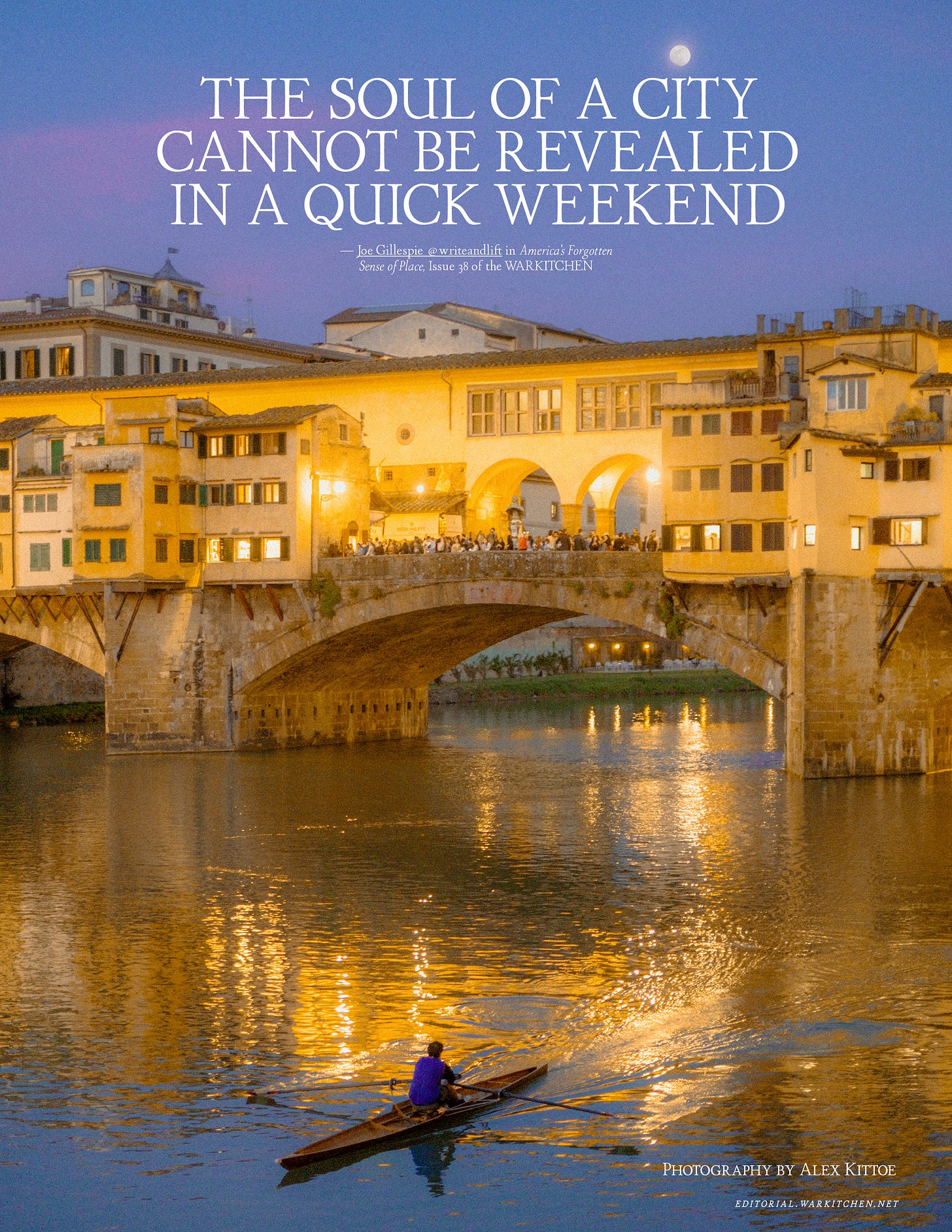

When we step off the plane in a city like Rome, our primary intention is to “take in” as much of the city and environment as we can in a condensed number of days. We have a bucket list of to-dos, a busy weekend ahead of sights and landmarks; maybe a guide—a curated window of experience—that lends perspective and contextual knowledge; a frame to inhabit, an easy solution to make sense of it all.

The tourist always has an idea of Rome. And their mission, in part, is to confirm that this idea is valid; that this sense of place constructed in their mind connects to tangible reality.

But for the Roman citizen, this sense of place will drastically differ. I’m going to assume that their “idea” of Rome isn’t waiting in long queues at the Pantheon or Coliseum, taking selfies at the Trevi Fountain, or eating at “tourist trap” restaurants in high-traffic squares. In all likelihood, it lives in the innumerable small memories and sensations of average daily life: the smell of the hundred-year-old neighborhood trattoria, the motorbike commute across the city in the early morning, the stark contrast of the monolithic concrete office buildings built by “El Duce.” There is a culture, aesthetic, and identity tied to time spent in a place that only a local can truly understand. The soul of a city cannot be revealed in a quick weekend, and it’s not supposed to be.

There has always been an unstoppable inertia in the face of change. The challenge becomes preserving the “Rome-ness” of Rome while balancing the economic needs of more stores, parking lots, or infrastructure. It can be done, but it requires conscious effort. For example, the historic city center of Dresden, Germany—which was obliterated by Allied bombing raids in World War II—was successfully rebuilt in the nineties. The medieval Frauenkirche Lutheran Church alone cost over 250 million dollars to rebuild. Indeed, it would have been more “economical” to build a flat modernist building in its place, but it would come at the cost of sacrificing the soul of the city and its people.

The story of Dresden is an anomaly. In America, change moves in fast, loud, and efficiently. The sense of place—and feeling of pride—that comes from living in (insert town or city name here) has become increasingly meaningless. It isn’t that our heritage landmarks have been stripped (though in some cases they have), or that there aren’t still quaint, walkable, interesting neighborhoods or districts. It’s that the rule has now become the exception. Our cities, towns, suburbs, and businesses have a liminal “nothingness” to them. A vague recollection of an idea of what a place should be and feel like, without any of its former soul or character that once made it beautiful, enticing, or unique.

The small-town general store, run by the Parker family for five generations, is converted into a Dollar General. The home improvement store in downtown becomes a Home Depot. The boutique hotel becomes a Best Western. The drive-in diner becomes a Sonic. And the list goes on.

Every town or suburb used to be a one-of-a-kind experience. Now, they’ve converged into a bleak and standardized form of corporate homogeneity; treeless housing developments accessible only by car, massive identical shopping centers dotted with big box stores and identical rows of boutique chain “anchor stores,” an industrial district of harsh glass office buildings and warehouses, and a small, but dying “historic downtown” or central business district where half an hour of parking costs three dollars.

If you’re reading this and saying to yourself, “Not my town!” Good for you. You’re an outlier. Cultural or economic trends are never absolute.

Assume a “some but not all” caveat here. But for the majority of us, who have seen our communities become vague copy-paste renditions of each other, the question becomes, what do we do about it? What can you do about it?

Create Your Sense of Place

When I think of The Shire from The Lord of the Rings, I’m filled with a sense of yearning and longing that I find hard to articulate. It is embedded in nature. It is tended and cared for; tilled and shaped by successive generations. The community is small and organized around shared values and interests (albeit with inhabitants slightly ignorant of the goings-on of the outside world). Natural resources are abundant, and communal spaces are places of friendship, entertainment, and hearty discussion.

Individually, we may not be able to bulldoze the new fast-food restaurant or prevent a developer from building another strip mall to build our Shire. Still, we can all do our part to recapture and rebuild a sense of place in our communities.

It starts by remembering what makes an environment human.

We are instinctually community-oriented. Not in a “Communist” sense; instead, our entire existence (up until this strange point in time) has been one of mutual cooperation with our neighbors. We want to solve problems together. We want to get to know our neighbors, support their businesses, and gather in shared spaces. Before globalization, the village, hamlet, and town acted as models for the values and culture of their inhabitants. (Seek a place that is aligned with your worldview. Think about the religious, demographic, political, and social dynamics.)

We are drawn to the natural world. Technology, as amazing as it is, dulls our minds like a drug. It takes us away from what is natural and good. Working in the sun, cultivating a small garden, playing at the park, and having the means and ability to build on our property connect us to the natural world that provides for us. (Seek a place where local or State government doesn’t criminalize or penalize you for growing your own food, building on your property, or—most importantly—drinking raw milk!)

Chance encounters foster community. When communities are isolated from businesses, schools, and shops, we’re relegated to the bubble of our cars. We walk less, and we don’t interact with the community as much. When we can walk from your house to the gym, school, or restaurant, we feel connected to ourselves and communities.

None of what I’m saying is of any value, however, if we’re unwilling to plant our feet. Not all of us are ready or willing to find “our place,” but if you are, you must choose wisely. Maybe it’s your current town. Perhaps it’s across the country. Regardless of where you choose, remind yourself that a sense of place emerges from the energy of those who inhabit it. Every place needs its champions. Its defenders. Its gardeners. Nothing happens by accident. It requires intention, daily choices, and small acts of conscious choice.

Start with your own property. Plant trees that will outlive you. Build with materials that age well—stone, wood, brick. Replace the vinyl siding with cedar. Tear up the concrete and plant a garden. Your neighbors will notice. Some will follow. This is how change spreads.

Support the holdouts. The family restaurant that's been there since 1962. The bookstore run by the old woman who remembers when downtown had twelve thriving businesses instead of three. The carpenter who still builds cabinets by hand. Every dollar you spend at the local diner instead of Applebee’s is a vote against homogenization.

Show up to the town hall meetings where they're debating whether to allow another chain store to replace the old hardware shop. To the community events that are small and poorly attended. To the volunteer fire department fundraiser.

Make your home a place people want to gather. Host dinners. Invite the neighbors for coffee. Create the third place in your living room if it doesn't exist elsewhere. Our great-grandparents understood this. A home should be a hearth, not just a storage unit for belongings bought on impulse from Amazon.

Resist the easy choices. Drive the extra five minutes to the family-owned grocery store. Pay more for the handmade furniture. Choose the local bank over the multinational corporation. Convenience is the enemy of character. Every shortcut you take speeds up the erasure of what makes your place unique.

Learn the history. Talk to the old-timers. Document the stories before they die. What was this place like before the interstate came through? Who were the founding families? What did Main Street look like in the 1930s? A place is built on its memory.

The sad truth is that most places are dying because nobody fights for them. We’re locked into our own lives with our own problems, unable and unwilling to think ten years into the future. We drive past the empty storefronts and shrug. We accept the strip malls and parking lots as inevitable. We move to the suburbs and complain about the lack of walkability, yet we refuse to walk anywhere.

But some places are different and you know them when you see them. Some towns still have character; neighborhoods where people sit on their front porches and know their neighbors' names. These places didn't survive by accident. They survived because enough people decided they were worth saving.

Your place could be one of them. It requires only that you plant your flag and don't let it become everywhere else. The developers and corporate chains are counting on your apathy. They're betting you won't fight for what you're losing.

You can prove them wrong.

Make your place a place again. Make it irreplaceable. Make it worthy of the memories your children will carry long after you're gone.

The world has enough nowheres already.

This piece was written by Joe Gillespie. If you enjoyed reading this, you’ll love his work. Subscribe to Write & Lift to read more of his musings. You can also follow him on Instagram @writeandlift.

Joe Gillespie’s piece was first published in Issue 38 of the WARKITCHEN. Read the full issue here. Explore the full WARKITCHEN archive here. Enjoy the experience 🥂

Thank you for this post! I appreciate your sentiment that the we used to physically engage with our world and now …

Share Your Perspective offers collaboratively created content on a ton of tough topics. Please check us out.