Strawberries, Cream, and Luxury: Wimbledon's Extravagant, Ultra-British Food History

A full menu of Wimbledon (and tennis)’s deliciously Victorian origins

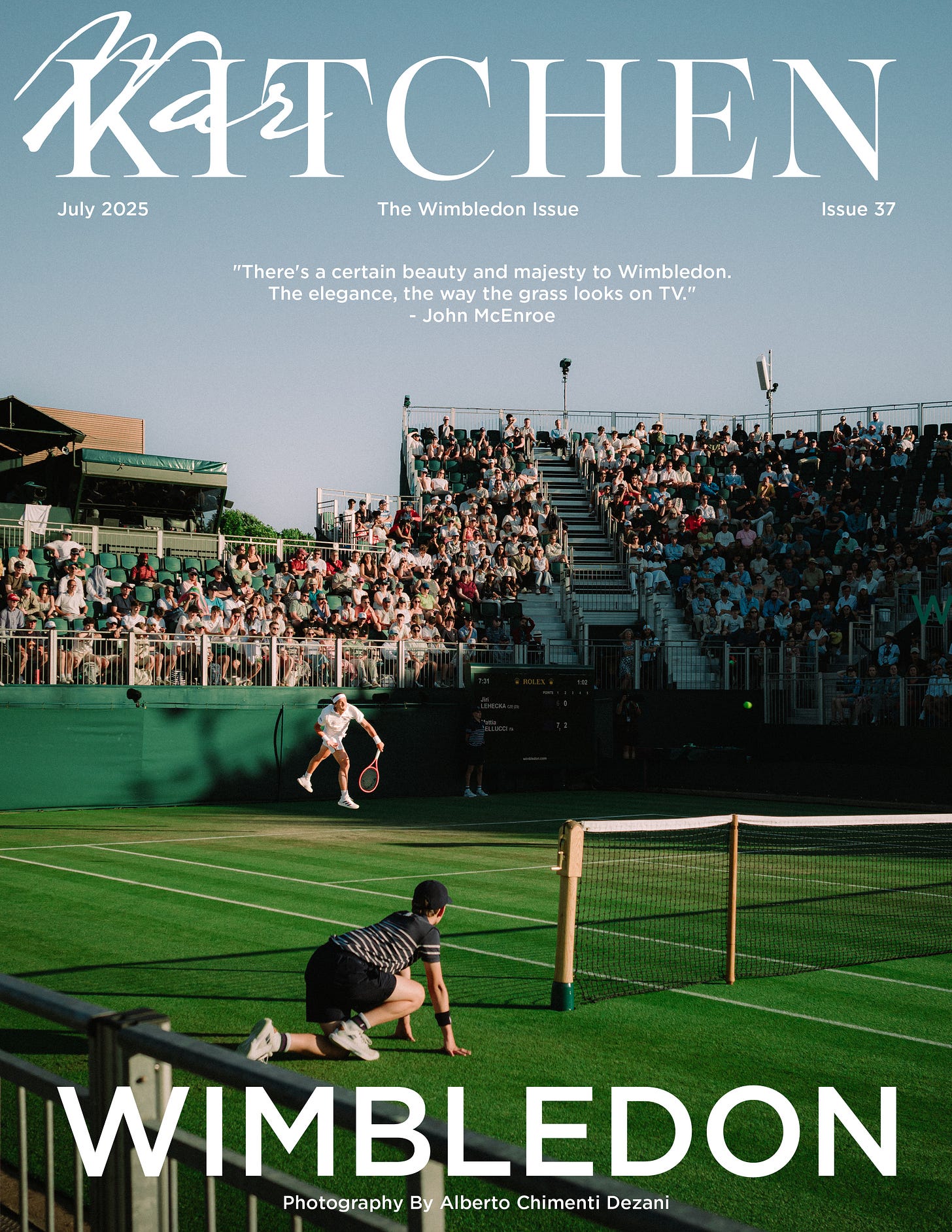

The natural beauty of tennis is magnified once a year. By returning to the nation of its modern-day origins, back to the sport’s traditional grass surface for its oldest, most prestigious championship, tennis’s splendor is put on full display for the world to savor. Wimbledon is tennis at its elegant core.

Watching the match requires a certain level of elegance, too—though occasionally, enthusiasm bubbles over etiquette. During the second set of the championship final between Carlos Alcaraz and Jannik Sinner, their showdown was interrupted when a cork flew from a champagne bottle in the crowd and onto Centre Court. Commentators joked, “What’s more Wimbledon than that?”

While certainly a faux pas, this moment speaks to the tournament’s unique air of conviviality. The food of a sporting event—however messily it’s consumed—paints a cultural picture of its attendees. Hot dogs and beer are standard for World Series spectators, southern elites sip mint juleps at the Kentucky Derby, and even the ancient Romans opted for walnut-stuffed dates during chariot races at the colosseum.

Wimbledon’s food traditions are grounded in British tradition, perfect for summertime, and simple in their delights. Elegant yet cheeky, you’ll see spectators sipping champagne straight from the bottle (via straws, at least) while snacking on handpicked strawberries bathed in fresh cream. Luxury taste is to be expected when the event’s trophy is awarded by the royal family, who’ve observed every final from the Royal Box since 1922.

Savor the history of Wimbledon’s menu below, starting off, of course, with drinks.

Pimm’s Cup

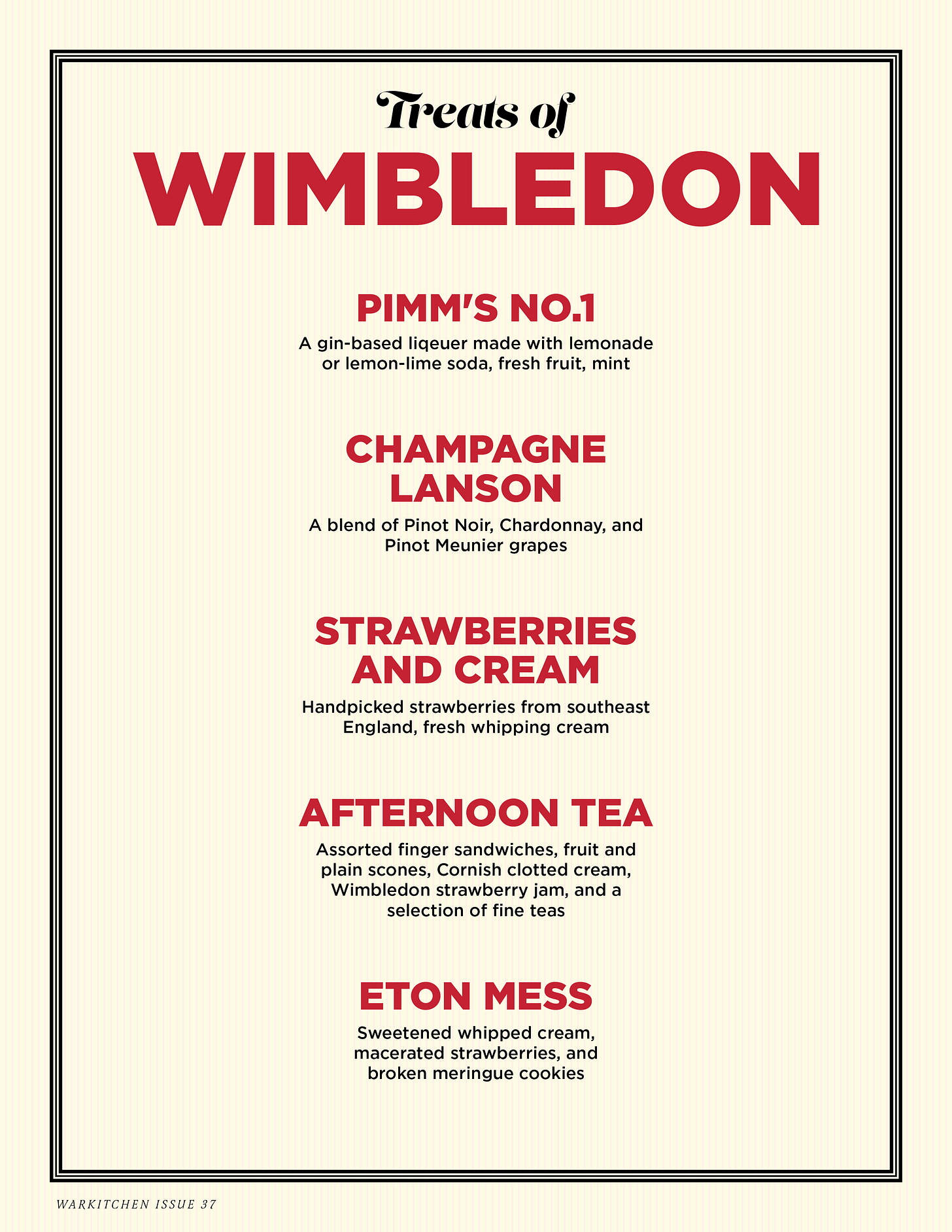

Pimm’s No. 1 (gin-based liqueur, lemonade or lemon-lime soda, fresh fruit, and mint)

Modern-day tennis has its roots in 19th-century England. Considered the father of “lawn tennis,” a retired British Army officer named Walter Clopton Wingfield sought to formalize “the ancient pastime of tennis” by making it playable on croquet courts. The sport became far more accessible and enjoyable to Victorian England, and soon enough, the rest of the world.

Another Victorian Brit aimed to improve upon a similarly ancient pastime: excessive drinking. London oyster bar owner James Pimm regularly experimented with making tonics, and hoping to aid his customers’ digestion, blended together gin, quinine, and spices in a large tankard that he called the No. 1 Cup. His clientele soon adored his herbal liqueur, and by the end of the century, Pimm’s was sold as a mixer throughout the country.

Eventually dropping its oyster associations, the “Pimm's Cup”—made with Pimm's No. 1, lemonade, and fresh fruit—has long been a British summer staple. While Major Wingfield’s work took over the globe, Pimm’s contributions reached far beyond Britain, too: interestingly enough, New Orleanians consider the Pimm’s Cup their drink, possibly due to British expat influence during the 1940s.

In 1976, “Pimm’s Bar” was established on the Wimbledon grounds, solidifying it as the quintessential cocktail for the occasion. Though another drink, the one with French origins, might be the more iconic order…

Champagne Lanson

A blend of Pinot Noir, Chardonnay, and Pinot Meunier grapes

Champagne isn’t just a celebratory staple but an iconic aspect of SW19. Champagne Lanson, chief supplier to the Royal Court of England since Queen Victoria, has been the championship’s official sponsor since 1977. It’s estimated that 25,000 bottles are popped at Wimbledon annually—some, at least this year, at inopportune times.

Champagne and tennis share oddly close roots: both originated in northern France and were created and/or refined by French monks. The monastic version of tennis (or “real tennis”) was called Jeu de Paume, or game of the hand, since the pre-racket version of the sport was played with bare hands. Tennis is thought to come from the French “Tenez,” which can be translated as “receive” or “take this!,” a warning shout from the server to their opponent.

Like serving for a set, opening champagne is a sort of controlled explosion. Sparkling wine’s fermentation process used to be a major concern: in modern-day Champagne, Benedictine monk Dom Pérignon was asked to nix the bubbles in vats of abbey wine to prevent barrels from exploding, which they had a dangerous habit of doing.

Thankfully, he didn’t get rid of them, improving upon the art of champagne-making instead by diversifying the grapes used in each batch and insisting they be picked in the cooler hours of the day. Timing is key, as much to wine as it is to tennis.

Some associate the sound of a cork popping with Wimbledon itself, its spirit of refined revelry. Champagne Lanson offers three key varieties of champagne: Black, Rose, and White. Le Black Label is the most popular, giving notes of “ripe citrus and orchard fruit,” while Le Blanc de Blancs features “delicate aromas of acacia flowers and candied citrus.” I wonder which label was uncorked right before Sinner’s serve.

But drinks are only half the fun of attending Wimbledon. What fruit better complements champagne than strawberries?

Strawberries and Cream

Handpicked strawberries from southeast England, fresh whipping cream

This simple dish is the most iconic of Wimbledon, made with just two ingredients: ripe strawberries and fresh single cream. It’s seasonal, exquisite, and traditional: a worthy representation of tennis itself.

Wimbledon is the sport’s oldest tournament, and thus it follows most of the original Victorian rules: an all-white dress code is enforced for all players. Originally meant to conceal the appearance of sweat (considered unseemly at the time), this clothing policy takes focus off of the players themselves and puts attention on their skills alone. The bright look of plain white tees, shorts, and skirts is stark against green grass; uniform and clean. It’s refreshing to the eyes in its simplicity. The silkiness of single cream, poured onto vibrant red strawberries, imitates this fresh contrast—and since there’s no sugar added to it, the sweetness of the berries takes center stage (or should I say court?).

Again, timing is everything at Wimbledon. Another rule some may consider archaic: an 11 o’clock match curfew. No floodlights—players must rely on the strength of the sun. Strawberry season occurs between late May and early July, so berries are perfectly ripe in time for the tournament. SW19 touts a long partnership with Hugh Lowe Farms in Kent—this farm, naturally, dates back to the Victorian era, too.

But the British love of strawberries and cream far precedes the 19th century, often credited to Cardinal Thomas Worsley’s dinner parties in the 1500s. The dessert was customary at English summer garden parties due to its timeliness and simplicity. Without means of refrigeration in the summer heat, the window of enjoyment (especially due to the cream) was narrow, making it a special seasonal luxury.

By the 19th century, railway development meant strawberries could be picked and transported to London on the same day—that level of freshness is maintained today. Wimbledon strawberries are picked before dawn on the day of serving, and after being shipped to the Club, are inspected and hulled before noon.

Afternoon Tea

Assorted finger sandwiches, fruit and plain scones, Cornish clotted cream, Wimbledon strawberry jam, and a selection of fine teas

Another Victorian-era invention (thank you Anna, Duchess of Bedford), this English tradition began around the same time James Pimm created his namesake tonic. After Wimbledon’s first championship in 1877, spectators found that tennis and tea were a natural combination, and the traditions quickly fused.

The prevalence of afternoon tea, with its wide array of sweet and savory treats to choose from, speaks both to wealthy British taste and the social element that fuels it. People gather not only to eat, but to talk—the same way esteemed attendees come to watch matches, but also to watch one another. Whether by eyeing royalty, celebrities, or the fashion of the British elite, there’s plenty to chat about while mingling over scones and sandwiches.

Afternoon tea is typically observed between three and five o’clock, and during a full day of spectating, it’s a much-needed break. Nothing’s more English than an Earl Grey tea (with its heavenly bergamot notes), paired with a Victoria Sponge cake or a Coronation chicken sandwich. Tuck in!

Delicious Traditions: Compliments of The Wingfield Cafe

Of course, there’s even more specialties to choose from: the Eton mess, another popular English dessert, was originally enjoyed during Eton College cricket matches (strawberries and cream make a star appearance here, too). Heavier fare beyond finger foods can include sausages, burgers, or the classic fish and chips, arguably the nation’s most beloved meal—an order of fried cod and thick-cut chips can easily fuel a day of matches.

Paying homage to the father of modern tennis, the Wingfield Cafe at the championship’s All England Lawn Tennis Club offers a wide variety of locally sourced fare to its tennis-loving clientele.

It seems this clientele keeps growing. Not only were Wimbledon tickets in uniquely high demand (a ticket to Sinner/Alcaraz match exceeded $20k on the resale market) but worldwide viewership was 31% higher than the past six years. Tennis as a pastime has exploded in popularity across America: the USTA reported a new high of 25.7 million registered players. One in 12 Americans played tennis last year, the highest proportion on record.

And it’s easy to see why. There’s no sport more innately graceful, unique in its etiquette, and attractive in its visual simplicity. Tennis’s newfound popularity, apparent in Wimbledon’s record-breaking viewership, could point to our generation’s growing hunger for meaningful aesthetics and straightforward beauty.

constanze price writes Coffee w/ Constanze, where she shares essays on travel, culture and passion. Read more of her work and subscribe here.

Constanze’s piece will be published in Issue 37 of the WARKITCHEN, a Wimbledon special. Stay tuned for the full issue!

Sources Used:

I adored this brilliant piece! It will inform my next day of luxury with my sister, which we usually enjoy on our birthday and following a strenuous event, such as a move or an illness. We never watch sports, though: It more often involves a work of Julian Fellowes. Or Mel Brooks.

Exquisite