The Fall and Rise of the Great American Bison

We nearly lost them, forever

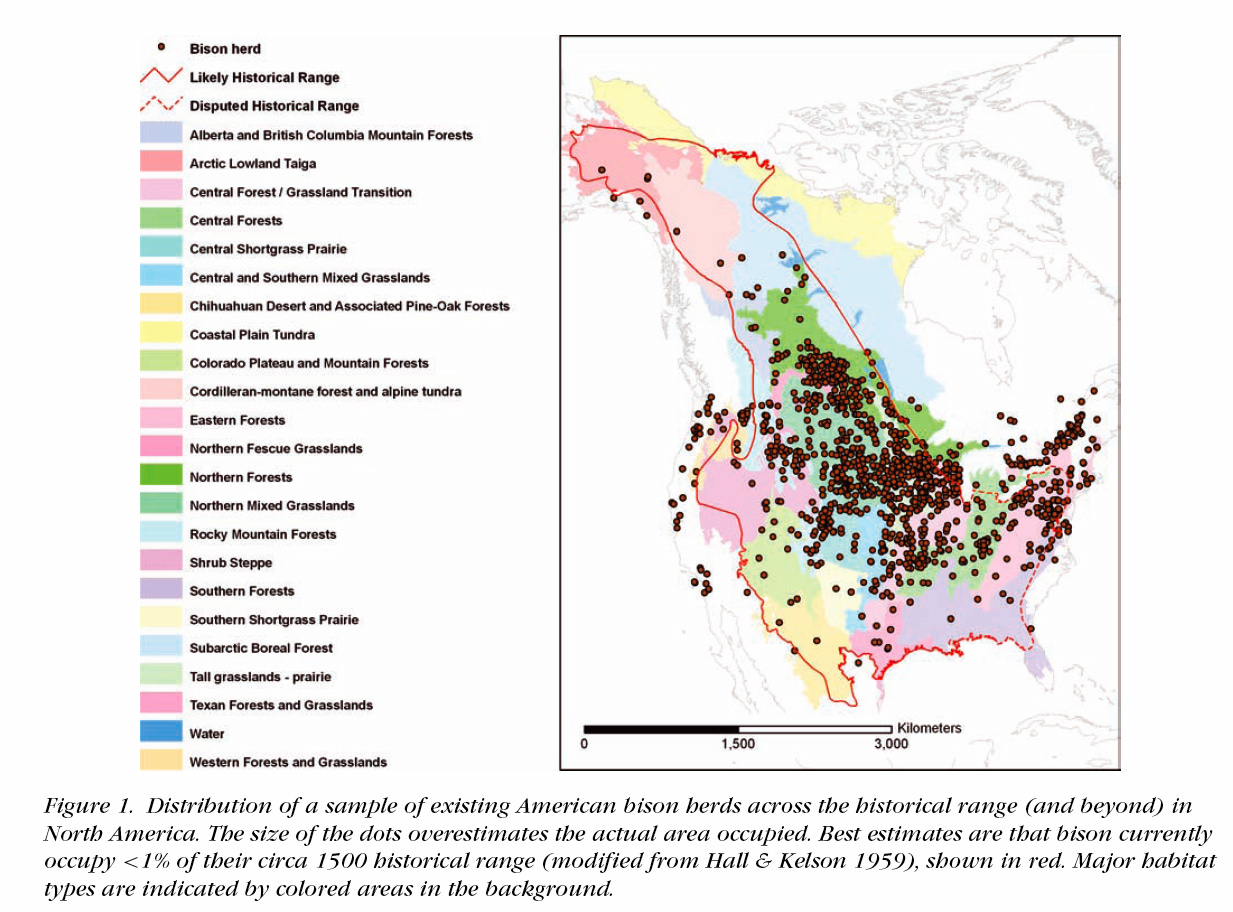

In 1799, in the heart of North Carolina, Joseph Rice, an early settler of the region, took aim and fired his rifle, bringing down the last known bison in the state. This moment, immortalized on a historical marker, signifies the many shots both literal and metaphorically taken against bison for over 400 years in the ecological and cultural landscape of America. The bison, once a symbol of abundance and a keystone species in the delicate balance of the American wilderness, would find itself on the brink of extinction during the relentless expansion of European settlers across the continent — before, remarkably, becoming a renewed icon of today. For centuries, bison roamed the vast grasslands of North America, their numbers estimated to be between 40 and 60 million in the 1500s. These majestic creatures, standing up to 6.5 feet tall and weighing as much as 2,000 pounds, were not only an awe-inspiring sight but also a crucial component of the ecosystem. Native American populations relied on bison agriculturally, utilizing every part of the animal for food, clothing, and tools. The bison’s role ecologically as a keystone species was equally significant, as their foraging habits helped maintain the delicate balance of the grasslands, supporting countless other fauna and flora.

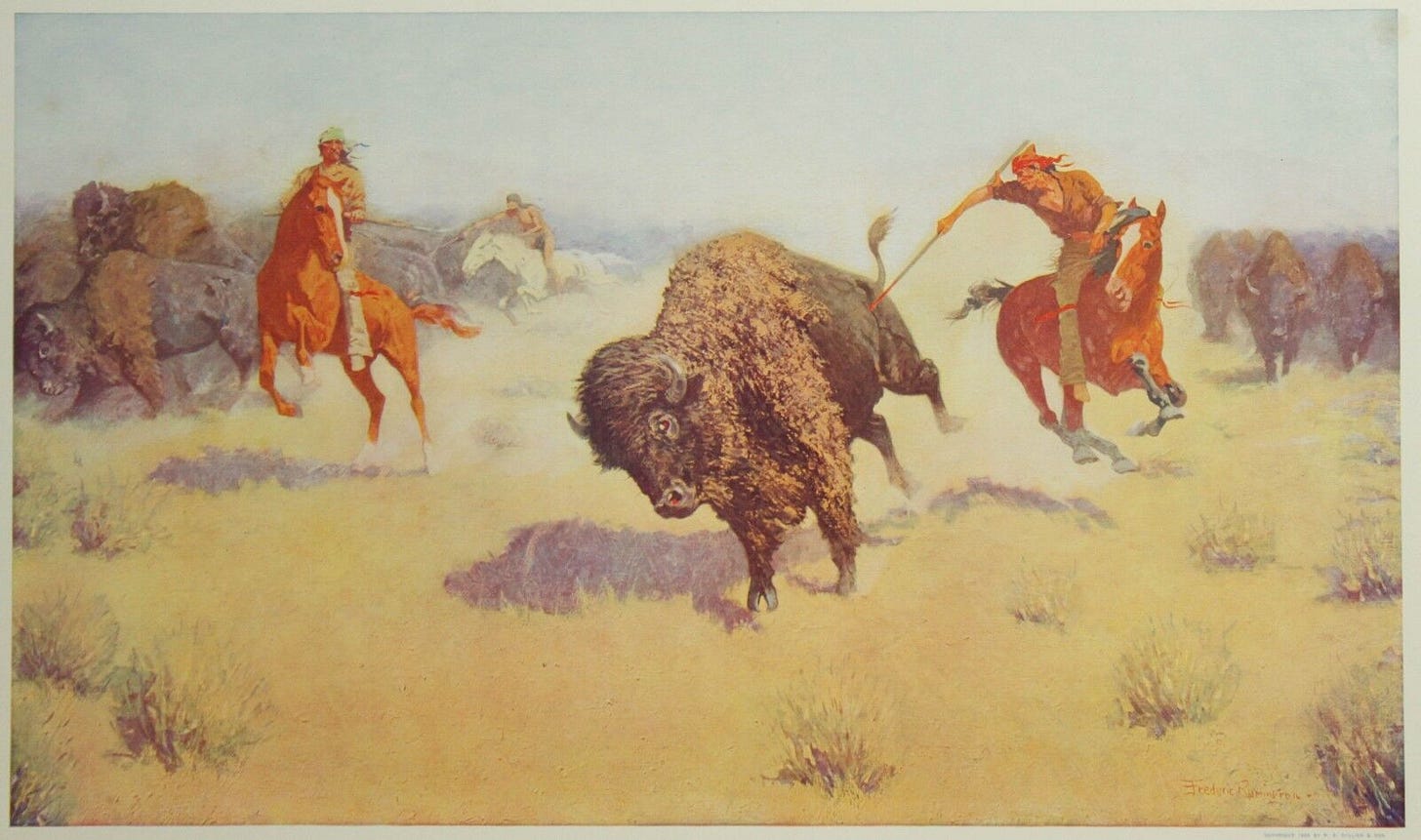

However, as European colonizers pushed westward, the bison’s fate took a tragic turn. By 1884, a mere 85 years after Joseph Rice’s fateful shot, the once-thriving bison population had dwindled to an estimated 300 individuals, teetering on the brink of extinction. This staggering decline was driven by various factors including overhunting, habitat destruction, and cultural shifts, and it forever altered the course of American history and the lives of countless indigenous communities. The bison, a symbol of the American wilderness, has a rich history that spans over 400,000 years. These magnificent creatures have played a vital role in shaping the ecological and cultural landscape of North America. Before the arrival of European settlers, bison populations thrived. As a keystone species, bison played a critical role in the grasslands of the continent. Their foraging habits, which involved consuming up to 24 pounds of vegetation per day, helped to maintain the diversity of plant life and create a mosaic of habitats that supported a wide array of wildlife. The bison’s impact on the landscape was so significant that it shaped the very evolution of the grasslands, with many plant species adapting to the grazing patterns of these large herbivores. For the indigenous populations of North America, bison were not only an essential source of sustenance but also a central figure in their cultural and spiritual lives. Native Americans relied on bison for food, clothing, and shelter, utilizing every part of the animal in their daily lives.

The arrival of European settlers marked a dramatic shift in the history of the bison. The pre-colonial North America was covered with bison, in regions far further east then originally thought. When Europeans began settling North America in regions like the east coast of the modern US, these populations were already dramatically lower then their peaks of 40 to 60 million — low enough for men like Joseph Rice to hunt them to extinction. Later years have clearer records: settlers brought new technologies, such as rifles and railroads, which allowed for the mass slaughter of bison and the reduction of populations to only a few hundred individuals remaining in the wild. But, all of this points to an unknown of what happened to bison populations in the 16th century, before European settlements.

There is also renewed hope for bison today, as there has been a resurgence of interest in the animals as a sustainable and healthy alternative to traditional livestock. Efforts of conservation and commercialization have led to the gradual recovery of bison populations, with nearly 500,000 individuals now found in commercial and conservation herds across the United States. This renewed interest in bison is largely driven by a growing awareness of the environmental and health benefits associated with bison meat production.

As the story of the bison continues to unfold, it serves as a powerful reminder of the relationship between human activities and the natural world. The rise, fall, and potential resurgence of this iconic species offer valuable insights into the ways in which cultural, economic, and ecological factors shape the course of history and the fate of the American wilderness. The dramatic decline of the bison population and its subsequent resurgence raises important questions about the complex interplay between human activities, cultural shifts, and ecological dynamics. As I researched deeper into the history of this iconic species, two primary research questions emerged, guiding my exploration of the factors that have shaped the fate of the bison over the past several centuries.

The first question focuses on the historical collapse of bison populations: How was the decline in bison commodity chains connected to the expansion of European colonial influence across North America? This question seeks to unravel the complex web of factors that contributed to the near-extinction of the bison, including overhunting, habitat destruction, and the disruption of indigenous cultural practices. By examining the ways in which European colonization altered the landscape and the lives of Native American communities, we can gain a deeper understanding of the forces that drove the bison to the brink of extinction.

The second question shifts our attention to the recent resurgence of bison as a consumer product: How is the modern growth in bison commodity chains connected to changing cultural attitudes toward health and the environment? This question explores the factors that have fueled the renewed interest in bison meat, including a growing awareness of the environmental and health benefits associated with bison production. By examining the ways in which shifting cultural values and consumer preferences have influenced the demand for bison products, we can gain insight into the potential for this iconic species to once again play a significant role in the American diet and landscape.

Together, these research questions provide a framework for exploring the complex history of the bison and the factors that have shaped its rise, fall, and potential resurgence. By examining the historical and contemporary forces that have influenced the fate of this iconic species, we can gain a deeper understanding of the ways in which human activities, cultural shifts, and ecological dynamics intersect to shape the course of history and the future of the American wilderness. The story of the bison, from its near-extinction to its recent resurgence, is a testament to the complex interplay between human activities, cultural shifts, and ecological dynamics. Through a careful examination of historical records, I argue that European expansion into the Americas led to a decline in native populations which impacted bison agricultural production systems and led to a cyclical decline in consumption, as native populations instead adopted European commodity chains around poultry, cattle, and swine.

The story of the bison is not merely a tale of loss and recovery but also a powerful reminder of the resilience of nature and the capacity of human societies to adapt and change in response to new challenges and opportunities.

The story of the bison does not end with its near-extinction. In recent years, we have witnessed a remarkable resurgence of this iconic species, driven by a growing awareness of the environmental and health benefits associated with bison meat production. This shift in cultural attitudes, I contend, is deeply connected to broader changes in American society, including a growing concern for sustainability, animal welfare, and the preservation of indigenous cultural heritage. Increasing attention on human and environmental health is now leading to renewed adoption of bison agricultural production systems into commodity chains of widespread consumption.

By tracing the complex history of the bison, from its central role in indigenous cultures to its near-extinction and recent resurgence, we can gain a deeper understanding of the ways in which human activities, cultural shifts, and ecological dynamics intersect to shape the course of history. The story of the bison is not merely a tale of loss and recovery but also a powerful reminder of the resilience of nature and the capacity of human societies to adapt and change in response to new challenges and opportunities. As we look to the future, the ongoing revival of the bison offers hope for a more sustainable and harmonious relationship between humans and the natural world.

In the following sections of this article, I explore through the captivating story of the bison, from its central role in indigenous cultures to its near-extinction and remarkable resurgence. We will begin by exploring the first contact between European explorers and bison, and how the subsequent decline in native populations led to a decrease in bison agricultural production systems and consumption. Shifting our focus to the 20th and 21st centuries, we will trace the bison renaissance, examining the contrasting approaches of the Tanka Bar and Epic Provisions in reintroducing bison to the mainstream market. We will then shift our focus to the current state of bison in modern society, discussing advancements in production technology, shifting environmental attitudes, and health considerations that have driven the cultural consumption and production of bison meat. Finally, we will reflect on the broader cultural shifts that have shaped the bison’s journey and consider its potential to become the new “American Meat.” By the end of this article, you will have gained a deep appreciation for the complex and often tragic history of the bison, as well as a renewed sense of hope for its future as a symbol of the American wilderness.

First Contact Then Decline in Production and Consumption

The story around food in the United States today for many Americans traces back to the so-called “First Thanksgiving”, when Pilgrims and Native Americans shared food in what would become modern day Massachusetts. Many staple crops for Native Americans such as potatoes, corn, beans, and more were integrated deeply into the American diet starting from that First Thanksgiving. And yet bison, which were once common in the region, were not present. Food native to America was already effected by colonialism even before the 13 Colonies were established. The First Thanksgiving was in 1621, over 129 years after Columbus landed in the Americas and the continent had already radically changed. Many groups of Native Americans once subsisted largely on bison, and yet modern US bison production is only about 0.14% of beef production. This section will explore why bison, unlike the staple crops native to North America, fell from use.

I first set out to understand the history of the consumption of bison, and why bison (which once heavily populated New England), was not present as the First Thanksgiving. For an understanding of what happened to bison, you have to start with how European colonizers first found them, and first impacted them. The first reference to a bison in European publication was as early as 1542 by Spanish explorers in Florida, noting an animal as the Bull of Florida for its resemblance to the bulls, aurorchs, and wissents found in Europe.

The art history text this was cited from, as an important development in the reception of the replicated printed image, notes sloppy inaccuracies in historical images and text about what was and wasn’t bison vs aurochs vs wisents, that continue to this day in the lexicon. This highlights a lack of scientific rigor and an implicit desire to oversimplify the environment that natives relied on when studying the Americas.

Around the same time as bison was first discovered by the Spanish, they were also making ventures farther into North America. Hernando de Soto and Juan Pardo explored the Appalachians, the Mississippi River Valley, and into what is now known as the Carolinas. This contact likely had the same effect on natives in North America, all of whom were unexposed to Spanish disease, as those in Mesoamerica. Mesoamericans populations, when first contacted by explorers like Cabeza de Vaca dropped upwards of 90% from before to after contact. These population changes were measurable and clear in Spanish colonies; however, in the uncolonized North American interior no Europeans had yet established permanent settlements, and thus no record could have been made.

This makes the argument difficult and in some ways circumstantial, but the effects of this population collapse can be seen in how the landscape in areas like the Carolinas changed. According to The Lost Supper, according to Pig Perfect, the first Spanish explorers in these areas found an “oak park of shaded grove, grassland, and scrub, [that] was eerily similar to dehesa”, but that later the “deep dark woods feared by the Pilgrims turned out to be a phenomenon of the European’s own making: … their germs killed the Indigenous people whose controlled burns made the forest more of a park-like dehesa”. For reference the dehesa was large swaths of Spain’s interior which had long been fenced off, where only sheep and pigs were allowed so that the pigs create a parklike landscape in what would otherwise be a dense forest. This created an extremely productive and sustainable ecosystem. For Natives living along the east coast of North America, they likely converged on creating a similar dehesa with a combination of controlled burns and large herds of bison. Native Americans acted with far more intentionality then just hunter gatherers, they intentionally crafted landscapes to make bison flourish and and thus make themselves flourish. They practiced widespread agriculture, using fire and bison together to maintain massive grasslands. Ironically, it was Spain’s arrival which led to the destruction of these areas to be replaced with dense forests and then later unsustainable farmlands.

In the Pilgrim’s early Massachusetts Bay Colony, bison was already rare and possibly even entirely extinct, and by 1732 when the 13th Colony, Georgia, was founded, bison were already extinct in the New England colonies.

As population and organized society collapsed, controlled burning and farming practices would have been been hard to maintain and natives may have turned towards overhunting bison to survive. This would have led to a cyclical process of overhunting, denser forests, bison going west, more overhunting, more population collapse, etc. Spanish colonial influence may have exacerbated this by restricting natives from practicing controlled burns, as they did exactly so when they established missions in California in the 18th century, leading to overly dense brush, and similar ecological issues.

In the 16th century, the Spanish spread disease throughout North America, causing 17th century populations of bison on the east coast to be in steep decline. By the 18th century, these populations would collapse or be forced west entirely. In the Pilgrim’s early Massachusetts Bay Colony, bison was already rare and possibly even entirely extinct, and by 1732 when the 13th Colony, Georgia, was founded, bison were already extinct in the New England colonies. Bison was sometimes eaten for subsistence throughout the colonies, but they were never able to develop a commodity chain for it because there was never any cultural demand for it. It was already in short supply by the time of widespread European settlement along the east coast. The niche that plentiful bison herds once fulfilled for native populations, was instead readily filled by cattle, swine, and poultry.

Bison Renaissance

My own interest in bison began, like many, in an interest in health. In 2019 I discovered Epic Provisions’ Bison Bacon Cranberry bar, offered as a healthy snack bar of 100% grass-fed bison meat, uncured bacon, and bittersweet cranberries. They’re delicious, and I can attest to reviews that they feed not only the stomach but the heart and soul as well.

Epic started in 2013 as a healthy snack company from Austin, Texas, not far from where I grew up. The brand and ethos of the company is something I strongly related to, and so I’ve consumed their various products for years. Yet, the story behind Epic and the Bison Bars they started with has more to it then many would expect. Epic started their Bison Bar in 2013, and today tout themselves as “the world’s first 100% grass fed meat, fruit, and nut bar.” Yet 6 years earlier, in 2007, it was the Tanka Bar that was the “world’s first”. I found it interesting that I had tried the Epic Bar years ago in a Whole Foods, yet the Tanka Bar seemed to no longer be for sale whatsoever.

The Tanka Bar was created in 2007 on the Pine Ridge Reservation of the Lakota tribe in South Dakota. It was a modern version of a traditional Native American food called “wasna” or “pemmican,” which consisted of a mix of meat and berries packed for sustenance on long journeys. The Tanka Bar aimed to promote a healthier, traditional diet among Native Americans, addressing the obesity and diabetes epidemic that disproportionately affects these communities. However, Tanka Bar’s strategy ultimately failed.

The creators of the Tanka Bar faced challenges gaining widespread marketshare. The Tanka Bar website from 2013 sells itself as made by Native American Natural Foods, the Lakota people, and uses fonts and colors and foods that has a deeply native feel to it. The branding is deeply native, and the appeals to health and the environment get lost in this. They initially focused on, and found amazing success in, selling the bars to Native American communities. Yet when they tried to focus on the broader U.S. market, the Tanka Bar brand found deep cultural disconnect and thus failure to market to American audiences. In contrast, Epic Provisions went on to successfully reintroduce bison to the mainstream market, even 6 years late to the market. The companies website pitches the founders’ story behind the company as witnessing the horrors of industrial cattle feedlots, experimenting with veganism, and ultimately reintroducing humanely-treated, grass-fed meat into their diets. The Epic Bar website from 2013, on almost the exact same date as the Tank Bar website, shows a stark contrast. Epic’s website and marketing is clear and directed toward health and the environment, with a clean white aesthetic that focuses on the consumer instead of themselves. Epic’s marketing strategy focused on what consumers care about: the health and environmental benefits of their products. This was extremely culturally relevant and forward looking in 2013, aligning with a broad consumer base and aligning with the growing interest in grass-fed, organic, and sustainable food.

The contrasting approaches of the Tanka Bar and Epic Provisions highlight the challenges and opportunities in the bison renaissance. While the Tanka Bar was rooted in Native American culture and tradition, aiming to promote health within Native American communities, it struggled to gain mainstream appeal. On the other hand, Epic Provisions focused on broader health and environmental concerns, successfully tapping into the growing market for sustainable, healthy snacks and appealing to a wider consumer base. As of 2016, almost 10 years after its inception the Tanka Bar was still sold in Whole Foods around the country. Yet at that same time, only 3 years after its founding, the Epic Bar had sold for a purported $100 million dollars. Tanka sold bison the same way it was sold in the 17th century. Only natives bought it. Epic sold bison to the 21st century. General Mills bought it.

Bison Today

Today, bison is decidedly mainstream even if it is not yet widely entrenched into American meat consumption. In 2016, Epic Provisions, the company which propelled the bison renaissance, was acquired by food giant General Mills for a purported $100 million. This acquisition is a strong signal of support and investment in the bison industry from a major player in the food sector. It demonstrates that bison is no longer a niche product but has captured the attention of mainstream consumers and large corporations alike. Bison’s resurgence can be attributed to its ability to fit into modern culture and agriculture. Advancements in production technology have made it possible to raise bison with minimal intervention and in free-range settings. Skaneateles Buffalo, a farm in Homer, New York, exemplifies this approach. The farm’s owners, Ellen and Tony Rusyniak, “liked the idea of natural grass-fed animals, and [they] liked the idea that they could be free range”. To ensure safety, the farm uses higher fences and relies on trucks or tractors when interacting with the bison, as the animals can be unpredictable and dangerous.

Shifting environmental attitudes have also favored bison production. There is a growing interest in sustainable and humane agricultural practices, and bison, as a symbol of the American wilderness, aligns well with these values. Bison’s role in conservation efforts and its ability to thrive on native grasslands have further contributed to its appeal. On the consumption side, health considerations have driven the demand for bison meat. Bison is leaner and higher in protein compared to beef, making it an attractive option for health-conscious consumers and those following specific diets, such as paleo or low-fat. As noted by Gary Murphy, a chef at Turning Stone, “If you’re health conscious, I definitely recommend eating bison”.

In the modern bison industry, two approaches to production have emerged. Traditional, grain-finished bison cater to mainstream consumer demands, offering consistency and affordability similar to the conventional beef industry. On the other hand, grass-fed, wild bison appeal to consumers seeking authentic, minimally processed meats, with an emphasis on environmental stewardship and animal welfare. These two approaches coexist, much like the salmon industry, where both farm-raised and wild-caught options are available.

The story of bison is a reflection of broader cultural shifts. Historically, bison faced near-extinction due to a cultural disconnect between Native Americans and European settlers. Settlers viewed bison as native beasts to be replaced by “civilized” agriculture, resulting in their lack of incorporation into colonial agricultural practices. The modern resurgence of bison is also reflective of changing societal values, such as increased concern for health, sustainability, and animal welfare, as well as a renewed interest in traditional food systems.

However, further research is needed to fully understand the impact and potential of bison in the modern food landscape. Statistical data and surveys on bison consumption and consumer perceptions would provide valuable insights into the current state of the industry. Additionally, exploring bison’s potential impact on rural economies and Native American communities, as well as its role in grassland restoration and biodiversity conservation, could shed light on the broader implications of this resurgence.

In conclusion, bison’s remarkable journey from near-extinction to cultural icon and culinary staple is a testament to the interplay between cultural shifts, consumer preferences, and agricultural practices. As a symbol of resilience, adaptability, and the evolving relationship between humans and the natural world, bison’s story is far from over. The future of this majestic animal and its place in American culture and cuisine remains to be written, but its clear that as bison continues to gain popularity and align with contemporary cultural values around health, sustainability, and animal welfare, it has immense potential to become the new “American Meat” of choice.

Just as beef rose to become the dominant meat in the American diet over the past century, bison now stands poised to potentially supplant cattle as the preeminent protein on dinner plates across the nation in the coming decades. Bison’s leaner, more nutritious profile appeals to health-conscious consumers, while its free-range, grass-fed production methods resonate with those seeking more ethical and environmentally-friendly options.

As awareness grows and availability increases through expanding commodity chains, bison could very well become as quintessentially American as the hamburger, capturing the imaginations and appetites of a new generation. The stage is set for bison to reclaim its place at the center of American food culture - not as a relic of a bygone era, but as a vibrant, vital part of the nation’s culinary identity moving forward.

This article was written by Conner Aldrich. You can reach him on X @semicognitive. If you enjoyed Conner’s writing and would like to read more of his work, you can subscribe to his Substack where he plans to write about AI and the world:

This article was originally published in Issue 26 of the WARKITCHEN Magazine:

Access the rest of our magazines and all of our links here. Godspeed 🥂