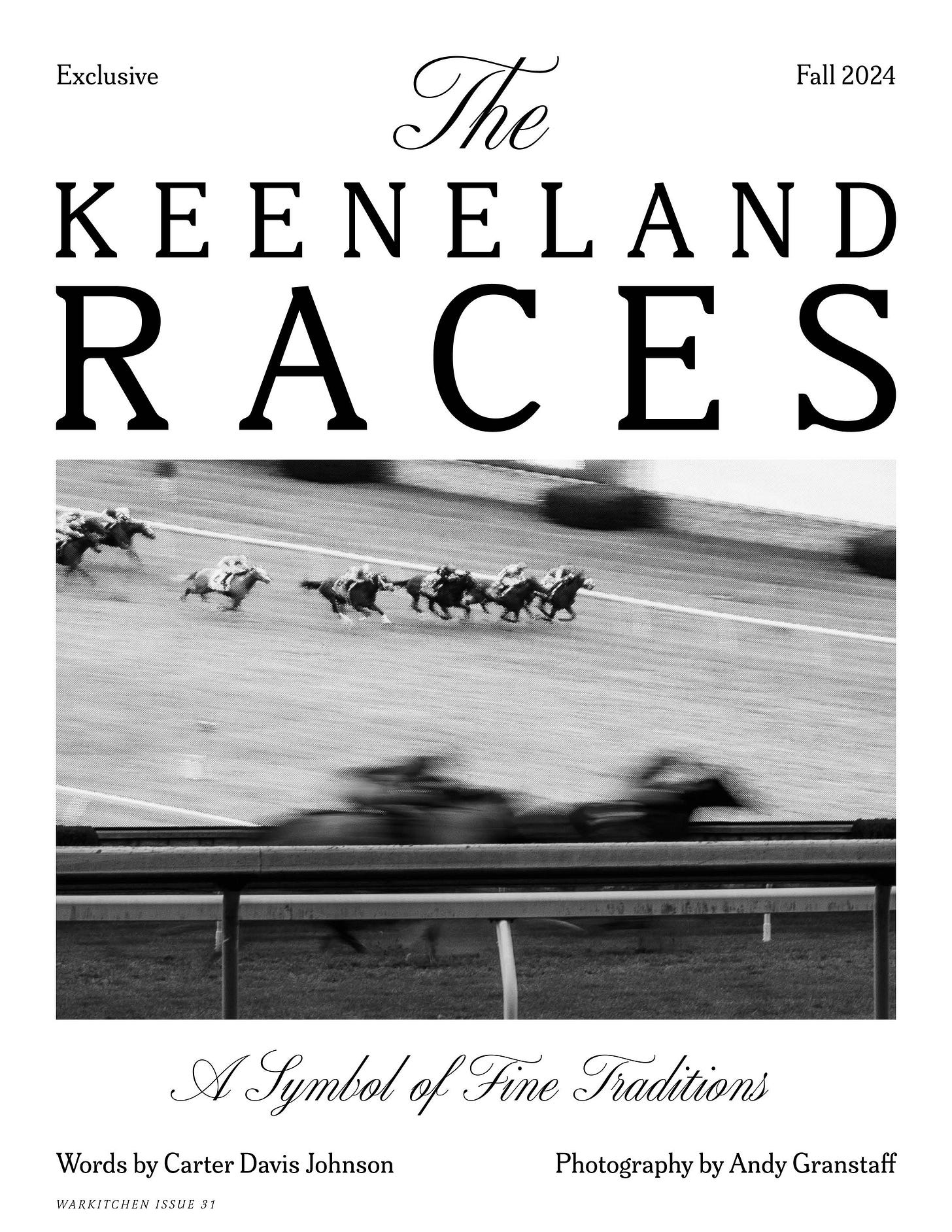

The Keeneland Races

A Symbol of Fine Traditions

Words by Carter Davis Johnson

Photography by Andrew Granstaff

The motorcycle purrs as I turn off the highway and onto Keeneland Boulevard. I downshift and lean into the gentle turns. The October air is still warm and a few crows, black and cacophonous, fly over the red maples and the pasture’s dull green. I give a little unnecessary throttle, just to feel it. I’m ready to be there, to leave behind essays that need grading and my tangled inbox of emails. Not this afternoon. Not at Keeneland.

My friend, Andy, is joining me to photograph the races and — more than that — the thing in itself, the too-much-at-once called Keeneland. He shuffles through rolls of film, hangs a Leica M6 around his neck, and puts two more cameras into a canvas bag. “That should be small enough to pass through security,” I say reassuringly, mostly to myself. A bag of cameras feels conspicuous. I mentally start preparing to defend our non-existent press credentials. We start walking toward the track.

Keeneland is a bona fide Lexington, Kentucky treasure. Although it was established during the Great Depression (1936), its mission was nonetheless young and idealistic: to “create a model race track to perpetuate and improve the sport and to provide a course that is intended to serve as a symbol of the fine traditions of Thoroughbred racing.” Nearly one hundred years later, the track has become the symbol its founding members dreamed about. We walk by the stables to the North Gate. Our bag of cameras is ushered in with a smile, and the staff compliments Andy’s shirt. As usual I’m wrong, but pleasantly so.

“Keeneland is a bona fide Lexington, Kentucky treasure”

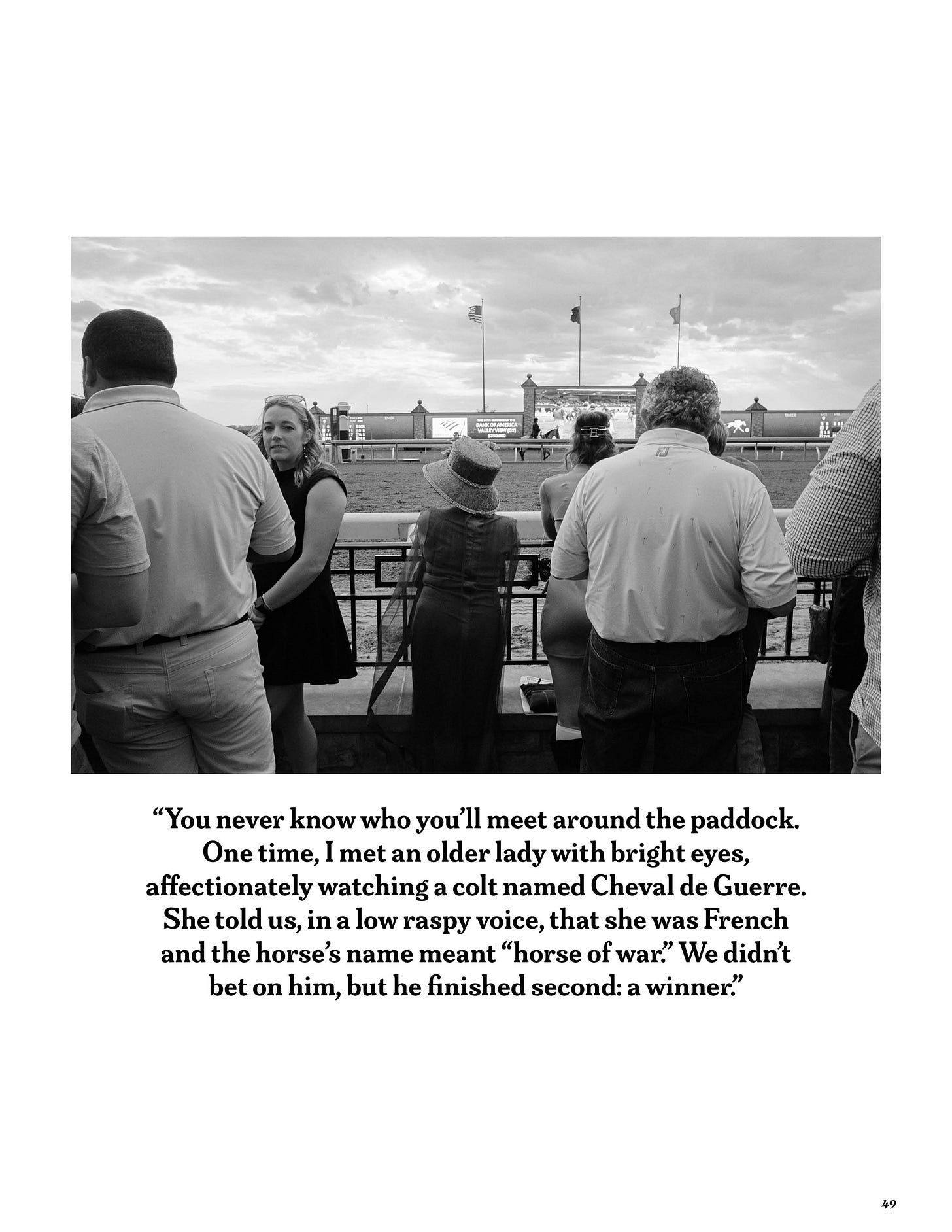

We pass under the branches of a black tupelo and join the crowd at the paddock. The thin smell of smoke mixes with the warm smell of horses and decaying leaves. Behind us, people flood through grey stone arches; above us, some suits sip cocktails on a terrace. I’d wager that the paddock is the best available field study for Western anthropology. The crowd moving around us rivals any long Whitmanesque list: businessmen on holiday, hustlers in zip-up sweatshirts, fraternity boys speaking in strange dialects, good-ole-boys with their largest belt buckles, small platoons of perky young women with dark lipstick and felt hats, middle-aged women trying to emulate said platoons, families with boisterous children, old geezers vice-gripping Coors cans.

You never know who you’ll meet around the paddock. One time, I met an older lady with bright eyes, affectionately watching a colt named Cheval de Guerre. She told us, in a low raspy voice, that she was French and the horse’s name meant “horse of war.” We didn’t bet on him, but he finished second: a winner. We shook our heads and tried to find her. She was gone. I’m not entirely sure she wasn’t a ghost or an angel. Who can tell about these things?

There are a few members of the “whisky gentry,” described by Hunter S. Thompson as “a pretentious mix of booze, failed dreams and a terminal identity crisis.” I get it. However, one can look upon such masks with less reproach than Thompson (who knowingly implicates himself among them). Such “gentry” and everyone in the crowd can be met with a warm Christian charity, a movement of the heart which Dostoevsky masterfully compares to an undeserved kiss. The stories are endless.

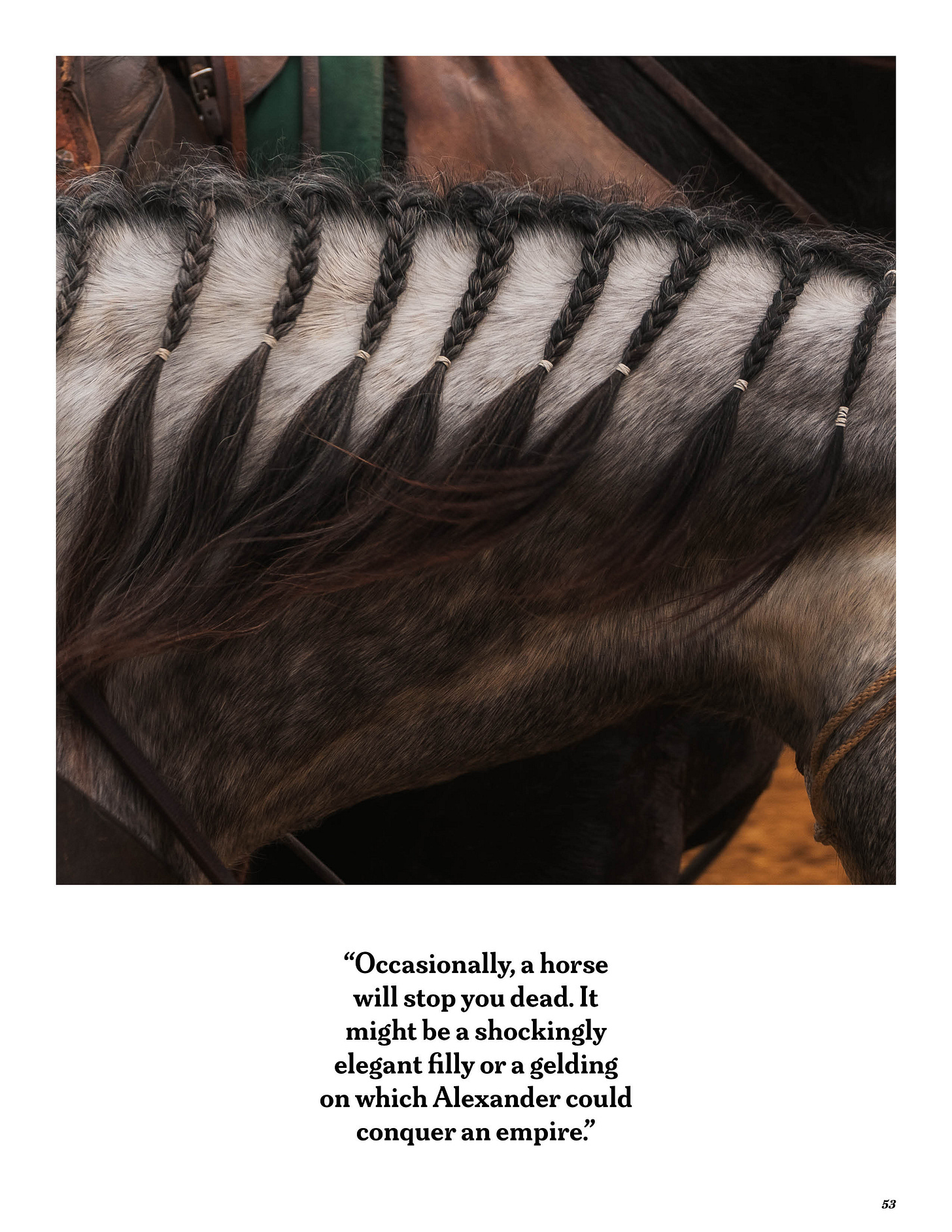

While the crowd is fascinating, everything revolves around the horses. As they turn slow circles, the speculation begins. Your eyes move from the program (training times, Beyer speed figures, class ratings) to the horses (walking steadily and stately) and back to the program (trainers, jockeys, win rates). If you read the names aloud, they sound like incantations from a drunken witch: Pharaoh’s Wine, Gilded Craken, Mo Stash, Neon Icon, Original Sin, Moonlight Gambler, Let My People Go. A good horse name is like good bourbon; it lingers. Handicapping horses (also like bourbon) is both an art and a science. While technical knowledge is necessary, there’s also the matter of instinct, gut feeling, and the unexplainable hunch.

Occasionally, a horse will stop you dead. It might be a shockingly elegant filly or a gelding on which Alexander could conquer an empire. You don’t know why or when, but the horse will just grab you by the lapels and shake you. Hemingway described a similar feeling: “He was being led around the paddocks with his head down and when he went by me I felt all hollow inside he was so beautiful.” I’ve always resonated with that description. Beauty — whether a spouse’s smile, a yellow chrysanthemum, or a stranger in the grocery store — appears unexpectedly and empties us. It’s an ache, a hollow fullness.`

I throw Andy’s canvas bag over my shoulder while he folds a spent roll of film. In the language of a non-photographer I ask, “You get some good ones?” He loads a fresh cartridge and replies, “I hope so.” The tentativeness of an expert. We walk toward the track.

On our way, I stop by the box and put a few dollars down. Cash bets are more gratifying than digital buttons. I mentally rehearse the bet before facing the teller, who is poised to quickly convert my money into little paper slips: “one-dollar exacta boxed on 7 and 8; two dollars on 3 to place; fifty cent trifecta boxed on 3, 8, and 7.” I smile because I already know these horses will break my heart. It’s like kissing a girl who is too pretty for you and you know it but you kiss her anyways and hope just maybe she’ll marry you and you’ll move to Europe. It’s sort of like that.

It’s busy this afternoon. We weave through the crowd and find an opening. The horses snap out of the post. Initially, everyone is quiet, watching the leaderboard and tracing the bobbing heads that appear across the infield. People careen to get a better view and re-checks their bets. I stand on my tiptoes. A slow rumble builds. As the jockeys make their moves on the final turn and straightway, the shouts begin, indistinct at first but then clear, “Go 4! Do it. Go 4!” The pound of the hooves blends with the crowd’s jumping feet. The shouts get louder. Andy peers through his viewfinder, shooting right between hats and heads. The outside horse comes on hot and charges in the last furlong. Everything hangs in the air. We collectively hold our breath when they finish, and then it’s over. The crowd responds with groans and cheers. It’s always both. If the favorite wins, the cheers beat out the groans.

If a long shot upsets the race, a few isolated and ecstatic whoops punctuate quiet murmuring. A few people look confusedly at their tickets. Did I win?

I already know, but I check anyway. Yes, two losing bets. I proceed with the ceremonial tearing of the slips. I like the way they flutter into the trashcan. The crowd is heading back to the paddock or getting in line for a hotdog, so Andy and I move right up to the rail. The horses walk by with their big chests pulsing and chuffing. Even the sound of their breathing is powerful. They’ve worked up a good lather and the sweat cuts channels in the caked dirt on their front legs and the moisture pools under their bellies before dripping onto the track below. Their veins are like the tendrils of an underground river, covered by a glistening coat that looks paper-thin. There is a thread between us, one that has existed for thousands of years. The sight of the horse snaps taut that string in my chest, one that is too often quieted by layers of digital callouses.

“It will be another six months before the spring meet runs in April. So, we’ll bury the experience under grey weather and wet snow. And we’ll wait. We’ll wait for Keeneland to rustle and resurrect when the dogwoods bloom.”

I haven’t a clue what the horse thinks about all this. I doubt he has a concept of winning. Certainly, he doesn’t care that he just won thousands of dollars. But I wonder. I wonder if he experiences a distinct pleasure in his race: the power of running alongside the others; the feeling of heat and speed; the bounce of the jockey’s light frame; the spit and snorts of the herd. I suspect he enjoys it.

After the day’s final race, Andy and I join the exodus. He spots a few missed opportunities on the way out, and I assure him, “Next time.” We ease into the crowd. The leaves are dying. The evening is dying. The fall racing season is nearly dead. It will be another six months before the spring meet runs in April. So, we’ll bury the experience under grey weather and wet snow. And we’ll wait. We’ll wait for Keeneland to rustle and resurrect when the dogwoods bloom.

Carter Davis Johnson writes Dwelling, a publication that embraces the non-identical in life and art. You can read more of his writing here.

Andrew Granstaff is a photographer passionate about visual storytelling primarily through the means of film. He loves documenting his family and life at home or anywhere the camera takes him. Check his work out at andrewgranstaff.com. You can also reach him on Instagram @andrewgranstaff.

This piece was originally published in Issue 31 of the WARKITCHEN

Excellent portrait of a special place. When I was about 9 my dad took me to Keeneland for the first time. After we placed a bet my dad told me, "Well this is your college money, son." Our horse lost the race. For several years thereafter, having no real understanding of what college was, I thought, "Well, I guess college isn't for me." On the way home we listened to Randy Travis. It was a great day.